James Gleeson: Surrealist painter, art critic and curator who drew dark inspiration from contemporary events.

James Gleeson was one of Australia’s greatest artists, and the country’s foremost surrealist painter. Unlike his contemporaries, who merely dabbled in surrealism, Gleeson remained true to its philosophy until his death at the age of 92. While his early work was critically acclaimed, in the middle period of his life Gleeson was better known as an art critic, author, poet and curator. At 68, he devoted himself to art full-time, and went on to produce more than 400 canvases.

Influenced not only by the great European surrealists, particularly Dalí and Magritte, but also by Freud and Jung’s theories on the unconscious mind, his work features nightmarish landscapes, full of violent and disturbing imagery. The early paintings, it is said, made women faint, and at least one hysterical girl had to be escorted from an exhibition.

Yet their creator was a gentle, unassuming man who spent the past half-century in the same modest suburban cottage in Sydney, sharing it with his mother, Isabella, then with his partner of nearly 60 years, Frank O’Keefe. Gleeson spent every morning in his studio, pausing only for a cup of tea, and although he was very frail towards the end, he was still working at a prodigious rate in his nineties. Honoured with a retrospective in 2004/05, “James Gleeson – Beyond the Screen of Sight” at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne and the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Gleeson was a philanthropist who bequeathed his entire estate – worth A$16m (£6.3m) – to the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW).

Born in Sydney in 1915, Gleeson grew up mainly by the sea. He lost his father, James, in an influenza epidemic in 1919 and was brought up by his mother. Gleeson used to say he was “born a surrealist”, and even as a child felt reality lay beyond the surface of things. Gazing into coastal rock pools, he was captivated by the hidden life within. “Inside were fantastic creatures. They made me realise what I thought I knew about things was only the beginning.” At 11, Gleeson was taught to use oil paint by his aunt, Doris McPherson, an accomplished amateur artist. He attended East Sydney Technical College, an art college, and became a teacher. But he continued to paint, and in 1939 exhibited his first work, City on a Tongue.

When he first read the philosophy of surrealism, “it just clicked”, although it was not until 1939 that he saw a real Dalí. Surrealism seemed an artistic language appropriate for a dark period that witnessed the rise of Fascism, the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War. In 1945, Gleeson painted his early masterpiece, Citadel, an apocalyptic vision deemed “too aggressive” to be included in his 1948 show at London’s leading surrealist gallery, the London Gallery.

Travelling in Europe from 1947 to 1949, Gleeson became inspired by the great classical masters. He explored mythology and religion in his subsequent work, but remained true to his surrealist roots. During the Sixties and Seventies, he was a prominent art critic and historian, writing monographs of, among others, the Australian artists Sir William Dobell and Robert Klippel (a lifelong friend with whom Gleeson shared a studio in London and who also exhibited in the 1948 London Gallery show). Gleeson also wrote poetry, and worked for several arts foundations and advisory boards. He helped assemble the collections of the new National Gallery of Australia, which opened in Canberra in 1982.

For 27 years, he painted only at weekends, mainly producing small works featuring male nudes. Then in 1983 he took to his easel full-time for his “final burst”, as he called it. He labelled his first canvas No 1. By the time of his death, he had passed No 450. This last phase of his artistic life is widely regarded as his most brilliant, yielding some truly monumental paintings, which Gleeson called “psychoscapes”.

He drew further dark inspiration from the atmosphere generated by 9/11 and the war in Iraq. One critic wrote of these works: “Representing an ineffable world in the furthest recesses of the human mind, these form an imaginary coastline, not of water, rock and sand, but a disturbing, organic morass of muscle, sinew, carapace, shell, hair and dripping membrane.” The director of the AGNSW, Edmund Capon, said this week: “James saw into our inner soul.”

A talented draughtsman who always began a painting with a drawing, Gleeson never really received the recognition he deserved, and the 2004 retrospective was belated. Some blame his subject matter. While near-contemporaries such as Sidney Nolan and Russell Drysdale focused on Australian themes, Gleeson described the world of the imagination. Gleeson’s bequest to the AGNSW was the largest ever received by the gallery. He said it was “my way of paying back to society what it provided to me… it enabled me to devote my life to art”.

In 2005, Gleeson said he still had hundreds of ideas for paintings. His works are held by all the leading institutions in Australia, while the British Museum has some of his drawings.

Kathy Marks

GLEESON, James Timothy (1915-2008)

Untitled, 1976.

Mixed Media on Paper

35x25cm

GLEESON, James Timothy (1915-2008)

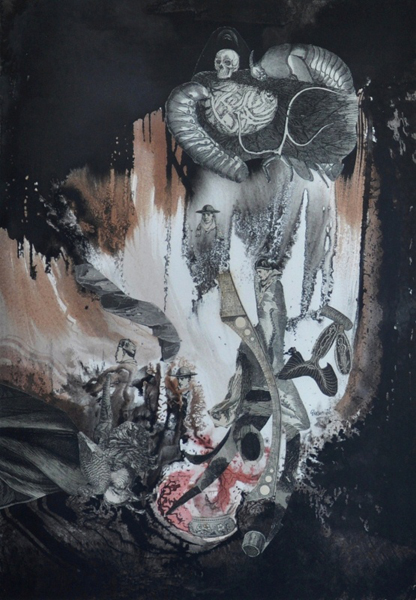

‘Those who dwell in the caves of the bad are unlike those of us who live in the houses of a city. (faux) Locus Solus, 1978.

Mixed Media & Collage on Paper

70x50cm

James Gleeson, painter, art critic, poet and curator: born Sydney 21 November 1915; Lecturer, Sydney Teachers College 1945-47; AM 1975, AO 1990; Visiting Curator of Australian Art, National Gallery of Australia 1975-78; died Sydney 20 October 2008.

Biography

Renowned as Australia’s foremost surrealist painter and poet, James Gleeson’s oeuvre explores the human condition beyond visible reality and the limitations of the senses through powerful enigmas of fleshy biomorphic, mechanical and illusionistic landscape forms. In addition to his contributions to surrealism, throughout his career Gleeson made important contributions to the Australian art world as a dedicated writer, critic and affiliate of a number of art institutions.

Gleeson studied at East Sydney Technical College from 1934 to 1936, and then at the Sydney Teachers’ College from 1937 to 1938 where teacher May Marsden encouraged experimentation. His interest in Poussin, El Greco, Breughel and Blake instilled a love of the classical figure and myth, coupled with a concern for humanity that was deeply impacted by the Depression, the rise of Fascism in Europe and the build-up to the Second World War.

From 1938 through the 1940s Gleeson experimented with surrealism and produced apocalyptic evocations of the destructive powers of human nature generated from this atmosphere of uncertainty and tension. Inspired by writers and artists including Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, André Masson, Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, he utilised poetry, dream, mythology and chance elements as material for his paintings, collages and drawings.

Referencing Jean-François Millet’s 1850 work of the same title, Gleeson’s The sower, 1944 presents a chilling twentieth-century vision of a ravaged rather than fertile landscape dominated by a conglomerate central figure, the dislocated limbs of which express humanity out of gear. In 1993, Gleeson reflected on the painting’s genesis as a reaction to the traumas of intergenerational warfare:

I think that there was always the hope that it could influence the way people thought about war. That it could alert people to its horrors and prevent it occurring again. You see, I was born during the First World War in 1915, and my earliest experiences were with people who were in that war or remembered the war very vividly, and then, just when I was beginning to paint, the Second World War began. So war became a kind of lurking terror in my mind from infancy through to late adolescence, when it was all building up again for another one.

Seeking to make surrealism better understood in Australia, Gleeson wrote and lectured during the 1940s, and spent two years travelling and studying in England, France and Italy from 1947 to 1949. In London, he shared a studio with the Australian sculptor Robert Klippel. Together the two collaborated on No 35 Madame Sophie Sesostoris (a pre-raphaelite satire), 1947-48 based on the figure of the ‘famous clairvoyant’ in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land whose enigmatic predictions of her tarot cards are alluded to on the four miniature panels at the base of the sculpture. The figure carved by Klippel appeared to Gleeson just the way he imagined Madame Sosostris would look and also reminded him in a satirical way of the mysterious, melancholy women who gazed from the paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne Jones. Gleeson titled the figure, distorted her name and cast her as a ‘pre-raphaelite satire’. Both artists grappled with concepts of the internal and the external and their aim with this sculpture was ‘to suggest the vital inner structure of an apparently simple form, to suggest that by some kind of x-ray magic one could look through the opaque skin and see all that lay within.’

From the 1940s through the 1970s Gleeson worked as prominent critic, writer and poet, writing for the Sydney Sun and Sun-Herald, and publishing seminal studies on William Dobell (1964) and Klippel (1983). He was also closely involved with the formation of collections at the new National Gallery of Australia in the lead up to its opening in 1982, and served on the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board and as Director of the Sir William Dobell Art Foundation.

Returning to painting in the 1980s, Gleeson developed a spectacular series of large-scale imaginary landscapes in which geological formations mesh with organs, bones and interconnective tissues, symbolic of a macabre, erotic but strangely beautiful subconsciousness. Executed in sensuous painterly brushstrokes, The arrival of implacable gifts, 1985 transforms J.M.W. Turner’s storm-tossed Slave ship, 1840 into a skyborne vessel dispensing mystery parcels onto a strange shoreline, evoking a cosmic experience of nature in constant evolution and metamorphosis.

In 1998 the Art Gallery of NSW held a focus exhibition on Madame Sophie Sesostoris (a pre-raphaelite satire) and an exhibition on Gleeson’s work entitled, James Gleeson: drawings for paintings, in 2006. Prior to his death in 2008, Gleeson and his partner Frank O’Keefe established the Gleeson-O’Keefe Bequest Fund which continues to facilitate the acquisition of major works of Australian modernism for the AGNSW collection, and honour the memory of Gleeson’s great contribution to Australian art.

Another rare James Gleeson C 1970.s this is a magnificent piece typical of James Gleeson’s earlier but brilliant work, this piece is from the estate of James Gleeson and was his personnel property for many years, the mind blowing inspiration and meaning that translates from this original work of art is simply amazing.

A James Gleeson original work of art titled “Untitled” 1978, there is a inscription with in the image, it is a deep and meaningful verse, the art work tonal range and mood is breathtaking and has infinite detail deep within, it is a complex yet simple work of art uniquely Gleeson, signed lower right in image and dated 1978, this piece was the personnel property of James Gleeson

About Locus Solus

Based, like the earlier Impressions of Africa, on uniquely eccentric principles of composition, this book invites the reader to enter a world which in its innocence and extravagance is unlike anything in the literature of the twentieth century.

Cantarel, a scholarly scientist, whose enormous wealth imposes no limits upon his prolific ingenuity, is taking a group of visitors on a tour of “Locus Solus”, his secluded estate near Paris. One by one he introduces, demonstrates and expounds the discoveries and inventions of his fertile, encyclopaedic mind. An African mud-sculpture representing a naked child; a road-mender’s tool which, when activated by the weather, creates a mosaic of human teeth; a vast aquarium in which humans can breathe and in which a depilated cat is seen stimulating the partially decomposed head of Danton to fresh flights of oratory. By each item in Cantarel’s exhibition there hangs a tale – a tale such as only that esteemed genius Roussel could tell. As the inventions become more elaborate, the richness and brilliance of the author’s stories grow to match them; the flow of his imagination becomes a flood and the reader is swept along in a torrent of wonder and hilarity.

Reviews

“Genius in its pure state.” – Jean Cocteau,

“An imagination which joins the mathematician’s delirium to the poet’s logic – this, among other marvels, is what one discovers in the novels of Raymond Roussel.” – Raymond Queneau,

“Raymond Roussel belongs to the most important French literature of the beginning of the century.” – Alain Robbe-Grillet,

“My fame will outshine that of Victor Hugo or Napoleon.” – Raymond Roussel,

“An experience unique in literature” – John Ashbery,

“The greatest mesmerist of modern times” – André Breton,

“Things, words, vision and death, the sun and language make a unique form… Roussel in some way has defined its geometry” – Michel Foucault,